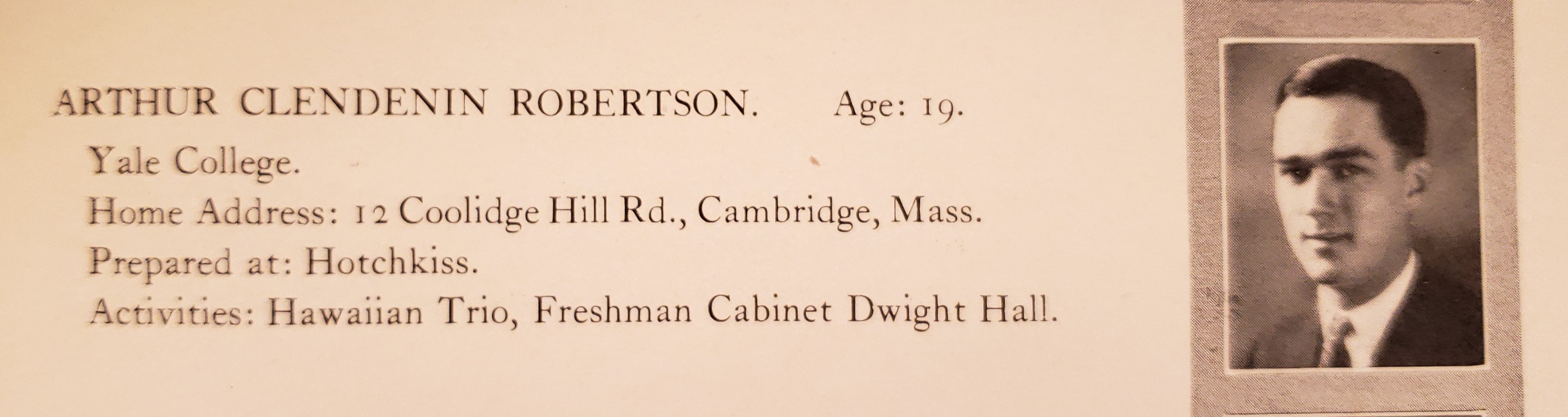

My father was a prolific letter-writer. What follows is an excerpt from his letter to – of all people – my mother’s aunt and uncle in March 1984, describing his travel to visit me in Taiwan and then our travel together to Mainland China. The letter concludes with my brother’s news, which I leave to him to share verbatim but which details his upcoming college graduation, potential graduate program with showers of fellowship money, and his choice between that and a job offer “at an outrageous rate of pay.”

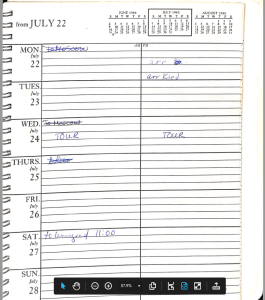

March 22, 1984

Dear Ben and Brenda:

It has been so long since I have had a chance to either visit with you or write but I thought it was about time to bring you up-to-date on our news. As you know, Amy is spending the year in Taiwan on her Fulbright/ITT scholarship studying Chinese law. I had a chance to visit her over Christmas for an excursion that took us to Hong Kong and the Mainland; and Ruth went for a somewhat longer visit at the end of January and they had an opportunity to go to half a dozen Asian countries.

I delivered a lecture at one of the law schools in Taiwan which Amy arranged. She and I had a great deal of fun working out the potential translation with the law professor who was both our host and our translator.

We decided to experiment to determine whether it is possible to visit Mainland China without either advance preparations or a formal tour; I am pleased to report that it is possible. A travel agent in Hong Kong (a friend of a friend of a friend of Amy’s in Taiwan) got us a visa in only 24 hours. We then went to the Hong Kong railroad station, and took a train to Canton.

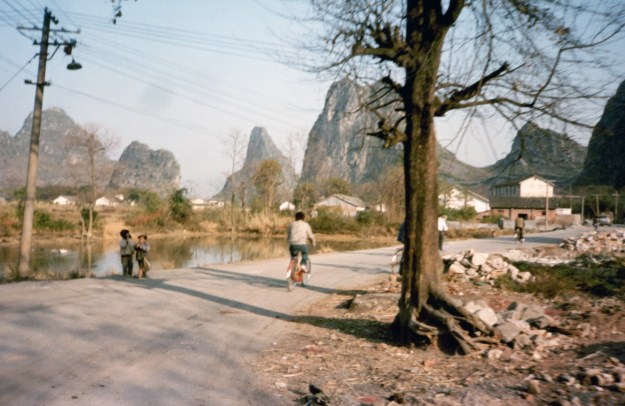

In Canton we went to the airport and purchased an airplane ticket to Guilin. Actually this stage wasn’t quite that simple. We first went to the downtown ticket office which told us nothing was available. It was the cab driver who said that we should ignore those bureaucrats and go to the airport because “something is always available.” He was right, at the airport Amy walked right up to the counter, purchased two tickets, and we got on our Boeing 737 and were on the way to Guilin and some of the most picturesque scenery in all of China. (I have since learned that they hold half the seats for government officials and release them at the last minute if nobody shows.)

We arrived in Guilin at about 8 in the evening, took the local bus into town, got off the bus, and walked six or eight blocks in the darkness to a hotel which had been recommended to us; and walked in and rented a room.

We were only there three days but, frankly, it was one of the most fun adventures I have ever had on a foreign trip. We rented bicycles and spent two full days touring around the countryside. On the first day we stumbled into a small village which was actually a teachers training college for students who would teach English. We spent three delightful hours with several students eating rice and stew warmed over a small charcoal grill in the middle of their dorm room — 55 unheated degrees. They had seen us bicycling through the village and had stopped us in order to practice their English. One of the most moving moments was when one the students, after having shown us his standard text with its typical English language sentences such as “the neighborhood committee assures that all the peasants carry out the teachings of the party leaders” (why, I use that vocabulary at least twice a day), proudly took a paperback biography of George Washington out of the back of his desk. It was dog-eared and obviously heavily read.

The next day we bicycled in a different direction and ended up following a road that turned into a smaller road that turned into a smaller unpaved road that turned into an even smaller, smaller dirt road that turned into a path that turned into a narrower path that ended up winding us for three or four miles literally down a two foot wide path among the farmers’ fields and provided us with an excellent opportunity to observe the agricultural process at very close range.

I sometimes wonder what Chinese peasants must have thought when they looked up and saw this American on a bicycle with a three piece pin striped suit, white shirt and tie, riding down a path through their fields. Actually, my fantasies were even greater when we passed a railroad crossing. I thought of some American tourist on a packaged tour traveling first class through China babbling on to his/her spouse about the “picturesque little peasants” when suddenly he flashed by this grade crossing on one of these country lanes and saw this American male in a three-piece pin striped suit on a bicycle and turned to his wife (whose attention meanwhile has wandered) to describe what he had seen; and received a “that’s right, dear” in a Thurberesquet so-you-heard-a-seal-bark tone of voice.

I thought you might enjoy a miscellaneous collection of some of our more interesting photographs and I am enclosing several:

[Amy’s note – my copy of the letter did not include the photos, but I think I’ve identified them and include them here. I have not included alt text as my father describes them below. In each, I am a mid-20s white woman with a really bad perm; my father is a late-40s white man in, yes, a pin striped suit.]

1. Amy cooking New Years dinner in Taiwan.

2. Amy buying plane ticket in Canton as we leave for Guilin.

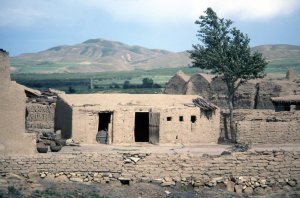

3. Amy arriving Guilin — note the characteristic mountains in the background. They really do have mountains like we see in the paintings. But then New England Lobster Villages really do look like the paintings — I don’t know what I expected.

4. Biking in Guilin.

5. Street side library in Guilin. Brenda, as a librarian, I thought you would find this of particular interest. Note the books hanging on a clothesline, the rack of books in the back left-hand corner as you face it, and another rack of books up front. As near as we could figure out they actually pay a small fee for the privilege of sitting and reading these books.

6. Amy looking at typical Guilin scene. [Couldn’t find this one.]

7. Amy and friend Ben from Taiwan. [Editorial privilege not to include photo of long-ago ex-boyfriend.]

8. Amy and the students we met in Mainland.

9. A local fisherman near Guilin balancing on his boat (which consisted of four long bamboo logs tied together and was not much different than balancing on a floating large sized diving board) as he strung out his nets. He sculled backwards with an oar in his right hand while feeding out some 200 yards of net from his left hand in a pattern that went back and forth across the river about eight times. Why, you might ask would one need eight separate layers of net. to catch fish coming down the river? Answer, the fish aren’t coming down the river. The fish live in a cave on the bottom of the river and after the nets are strung out the fisherman makes noise and scares the fish out of the cave and they come up in between the various webs of the net rather than being trapped by swimming into the net end wise. I wished I could have taken a movie of this operation because the grace with which he sculled backward with his right arm, fed the mass of net out neatly with his left hand, while balancing on his diving board all the while was astounding.

Soon after I got back from China, Ruth went over and spent several days with Amy in Taiwan and they then spent close to two weeks traveling to a number of countries and ending up in Singapore on the Washington birthday weekend. Just as they were about to leave their hotel for the airport Amy’s pocketbook with tickets, money, passport, credit cards and camera was stolen and she had to remain behind to obtain replacements when Ruth headed out. Amy is apparently a miracle worker or, at least, has figured out how to function in the Asian culture. She was able to get replacement tickets without paying for them, (it usually takes four months); get the American Embassy to open up on Washington’s birthday and replace her passport (it usually takes three days and cannot start until after the holiday); and she made arrangements through the law firm where she works in Taiwan to get somebody who lives in Singapore to lend her $1000 cash American money. She spent three days dealing with these loose ends and then headed back to Taiwan — her adventure over. I think poor Ruth suffered worse — what with the imperative of her own plane schedule meaning that she had to go to the airport and leave Amy behind within an hour after the theft. Even though Amy was doing very well, Ruth was isolated on a plane for eight hours and she had no way to know that things were working out ok.

Amy here, adding two more photos. First, my father teaching the law school class he discussed in the letter. He is bundled in a winter coat, as Taiwanese classrooms were not generally heated, and is pointing to a blackboard with notes of anti-discrimination remedies. A photo of Sun Yat-sen is hanging high on the wall on the right. The second photo is of my father and me in Guilin, possibly the two dorkiest American tourists ever to visit China.